These recommendations are written for anyone concerned with the forced closing of their school, including community members, school administrators, families, students, and residents without school-age children. Some might be more useful for school leaders, others for community members.

Below, I’ve identified strategies that have worked to stop school closures, especially those forced by state policy. Click on each to find out more information and details.

For these tactics to work, you will need a good organizing strategy. By organizing, I mean deliberately building relationships, establishing leaders, holding one another accountable for the work you agree to take on, and mobilizing people to create change for a better, more just future. This will take time, energy, and courage—but without organizing, you’re unlikely to build the power and momentum needed for real change.

A final note: start early (early = 5-10 years before closure would likely occur). It is much easier to prevent a closure than to stop one that’s already happening.

The tactics

Understand the issue and develop a plan. Spend time understanding what’s making closure a threat in your community and developing an action plan to counter it.

- Understand the issue. Do research and collect information to find out: 1) what policy or issue could cause your school to close, 2) when that closure could happen, 3) who would be responsible for that decision (school board? Voters? The state?), 4) how to reach those decision makers, and 5) what the research says about the effects of closure on students and communities.

- Develop a plan. Once you understand the threat, bring a diverse group of stakeholders (e.g., parents and non-parents, youth and elderly, school administrators and town leaders, community members of all races and classes) together to develop a plan to avoid closure. This plan should work on a couple of fronts simultaneously. For example, if there’s a state policy that causes consolidation of districts with low enrollment (which typically leads to closing one or more schools in the district), then craft a plan to increase enrollment AND to get the state policy repealed.

- Target your efforts. Closure might also be a somewhat complex series of events with a variety of decision makers, like a particular state policy (e.g, graduation standards, facilities requirements) causing fiscal distress locally and making the local school board consider closure. You might need to wage a fight on two levels: locally, to forestall a school board voting to close, and statewide, to change state policy. But it is crucial to know WHO to target in your organizing efforts and focus your energy there. Time spent convincing the media, for example, doesn’t matter if it’s the school board that makes the decision and they don’t care what local media have to say.

- Act early!!!! Some of these recommendations—like trying to increase revenue, for example—are most useful when closure is only a distant, distant threat, like 5 to 10 years down the road. Pay attention to certain universal triggers, like long-term declining enrollment, long-term increasing cost per pupil, deferred maintenance of facilities, and sustained increases in local property taxes for education; these triggers require action (education and organizing) BEFORE closures are proposed..

- Understand the opposition. Who’s opposed to keeping the school open and why? Know their doubts and weaknesses, too, and leverage those.

- Coordinate school and community efforts. Closure is not something just for school leaders to worry about! It also requires the coordinated work of community leaders, formal and informal, including town/city council members, religious leaders, youth leaders, elders, etc.

Educate, expand, and organize your base. Create a community around shared values (educational justice) and goals (keeping your school open). Then focus on multiplying this base and organizing it to take action.

- Create a community group. This group should build local awareness of school closure and its likely impacts. Recruit anyone who has a stake in the issue, including all ages (kids to elderly). Sharing stories about the school, experiences in it, and what it matters can be a powerful way to build and mobilize this base.

- Identify leaders. Know who has the confidence of your base: those who are committed to the issue, who can unify others, who will act and rally others to action. They are reliable, accountable, and action-oriented.

- Then expand your base. Reach out to those who aren’t on board with stopping closure—find out what their interests are and speak to those. Designate ambassadors whose job it is to knock on doors and recruit converts. Have pop-up meetings in places that people already go (churches, mosques, farmers markets, before basketball games, library story hour, the local diner). Use one-on-one meetings to recruit new members.

- Involve youth. They have the most at stake, and their experiences should be centered.

- Increase community attendance at community and school events, including town council meetings and school board meetings. Organize caravans and carpools to town/city council and school board meetings. During public comment, bring up closure as an issue: what steps are leaders taking to avoid closure? What is the timeline? How can the public get involved? Even if people don’t speak up, their presence indicates how important this issue is.

- Talk about it. Make sure EVERYONE knows that school closure is a threat. Talk about the issue—what the effects of closure would be, how the community is working to avoid it, and what they can do to help—with friends and neighbors at the store, at the gas station, at church—everywhere.

- Expect dissent and disagreement: not everyone in the community will want to keep the school open. Identify those dissenters early, and deploy friends and neighbors to persuade them or, at least, to neutralize their influence.

- Listen. The first skill of organizers is to listen, especially to the people who need to be convinced. Identify their values: what matters to them? Then frame your message in words that appeal to their values (e.g., thriftiness, wealth) and interests (e.g., keeping taxes low, economic growth). You can change attitudes faster if you run with, not against, people’s values.

- Know how to frame your message for your audience. It’s often not enough to say, “You have grandkids in the district, and so you should be willing to pay more in taxes.” You also need to speak to broader economic concerns: how does keeping a school open help the bigger economic picture? Make sure to include community members who do not have children in the school. If the debate about the school’s future gets polarized between parents and non-parents, it’s likely to fracture the community, as well as get the school closed. Speak to their interests and values in discussions about keeping the school open: what’s in it for them?

Build a coalition. Alliances for shared action are necessary in the fight for change.

- Find partners. What other organizations, groups, and communities might have interest in this fight?

- Identify shared interests and goals. Why should these other groups also care about school closure? How will closure impact them? Together, develop a message and make sure everyone stays on point.

- Create a shared plan of action. What are you asking people to do? Who needs to be involved (i.e., the target)? What’s the time frame? Why should anyone care? Anticipate the possible risks of action and have a plan for addressing those, too.

- Work with the local chamber of commerce. Together, identify the economic issues, such as lack of housing, that might impact student enrollment or teacher recruitment. Chambers might be able to coordinate business responses. They can also encourage members to support the schools by, for example, buying advertising to build a ball field or offering discounted rates for school bus maintenance.

- Reach out to other communities. If you’re pushing for policy change, it’s especially important to build a coalition of communities that will join in this campaign. The only way that small, rural communities (especially low-income and Black and Brown communities) can build the power to wage an effective fight in the statehouse is if they build up their numbers and then show up, make their voice heard, make a clear demand, get media attention, and force change.

Communicate well. Know your message, and keep it short, clear, and action-oriented.

- Develop a communications plan. Survey families and community members to better understand where they get their information about the school, what they want to know more about, and where they don’t feel heard. Use this information to develop a proactive and effective communications strategy.

- Keep your message is positive and action-oriented. Rather than simply saying, “Enrollments are dropping! Our school is going to close!” consider this message: “We know that enrollments have dipped in recent years, and, if this continues for the next 5-10 years, this could force our school to close. However, we have a plan. We are doing X, Y, and Z, and we’d like you to get involved by doing A, B, and C, so that we can all enjoy a school that is strong, growing, and good for our community.”

- Speak to people’s values. Frame your goal (e.g., getting them to take a specific action in order to keep the school open) in terms of their values. Use their words to get them to do your action. (See this great presentation from rural organizer Marty Strange on effective communication.)

- Tailor your message to your audience. What will persuade a tax-paying senior might be different than what persuades a parent concerned about their first grader’s future. State policymakers might care little about grandparents’ involvement in schools—but they do care about the state’s economic outlook. Know your audience’s specific concerns and speak directly to those concerns.

- Balance your communication. Make sure your outreach plan includes both one-on-one communication (with individual parents, community leaders, etc) and mass communication (to the entire community or, if relevant, the state).

- Address misinformation. Families make decisions about where to send their children based on available information, even if this is information is just hearsay. Make sure to combat any untruthful rumors directly, quickly, and with facts. Gossip about closure travels especially quickly, and it can also cause families to pull children from the district (who wants to enroll a kindergartner in a school that’s about to close?). Make sure that people have accurate information so that what folks are hearing is truthful and timely, and everyone understands the plan to avoid closure and address any issues.

- Be thorough in your communications. Make sure to post relevant information in a variety of places (from Instagram to the post office) so that ALL residents have access. Also, hearing information is often more effective than just seeing it—so ask local pastors, librarians, and business leaders to also convey your message.

- Tell the good stories. Make sure that positive stories about the school are reaching the public. To be clear, I’m not recommending suppressing bad stories or covering up issues that need to be addressed; instead, I’m encouraging you to spend time telling the good ones too. We often lose sight of the successes, and this can encourage school-bashing, making it harder for voters, school board members, and/or legislators to support keeping it open.

- Hold community forums. Forums to communicate information about closure and the plan to avoid can be a useful alternative to school board meetings. These forums should be offered at times that are good for community members, provide childcare and food, and avoid education and legal jargon. They can provide information about school closure, the plan to avoid it, and how community members can help. They can also address other issues of concern to families, especially those that might be causing families to leave.

- Change the debate. Discussions about closure often focus on the benefits of closure and the costs of staying open. Refocus on the costs of closure and the benefits of staying open. Be specific, and include the little things that are actually quite important, like the annual beans-and-greens supper or the ability to visit your grandkids at school.

- Bring up hard questions in public spaces. Ask the legislator: How far are you willing to let a young child ride on a bus? Why is my school getting closed when that other school is staying open?

- Involve local and state media. They can be an effective mechanism of getting your story out there, framing the message, building a coalition, and putting pressure on local and state officials. However, it’s critical to stay on message when talking to media, as media can also amplify division and disagreement; also, make sure the “action” you’re asking for and who you’re asking it of is clear.

Use research effectively. As one researcher told me, “If anything’s going to happen, it’s not going to be because some pinhead with a PhD comes in with some nice tables and graphs and persuades the state that this is harmful.” He’s right—it’s good organizing that works. But research can be a useful tool in an organized fight against closure.

- Know the research. There is a lot of misinformation and assumption around school closure. Know what the research says and use it to address partial truths or lies. For example, despite the widespread efficiencies often assumed to come with district consolidation (which can lead to school closure), several major studies say consolidation doesn’t save money. Also, the individual tax savings assumed to come with closure are often over-estimated. Finally, know that most statewide econometric modeling studies that talk about “optimal” or “most efficient” school size are based on statewide models, and they’re not meant to be applied to specific districts. So look at the numbers and the impacts within your own specific context, and give taxpayers and voters accurate information.

- Make the research accessible. Create a short one-pager that anyone can understand that describes the effects of closure and what action you’re seeking (e.g., policy change, school board vote), and then get it to the people that are needed to take that action (e.g., legislators, school board members) and those that can hold them accountable (e.g., voters). Short presentations (see this one to use and adapt) are also useful.

- Keep it local. You also need to speak to the local effects. Elected officials, especially local ones, don’t care about research; they want to know what will happen to their specific community. So do some local research, document what you learn, and create short one-pagers and community presentations to communicate your findings. Include anecdotes and personal stories, as well as numbers and figures to support your points. Here are some areas to investigate:

- Local impact on bus rides. Some communities have successfully fought closure efforts due to the implications for bus rides. So, what will happen to bus rides if the school closes? Talk with current bus drivers who can help you estimate likely routes and ride times. Think about safety, too, including road conditions, weather, and speed limits. Interview parents that will have to put their small children on a bus before daybreak.

- Local economic impacts. Speaking to the economic impacts can persuade some folks, including those who might not have children in the school. Identify local businesses that would be hit hard by closure. Who does business with the school (e.g., gas stations, banks, restaurants)? How much business do the school and its activities provide? You can ask business owners to estimate the revenue the school generates, or you can even track this information yourself—for example, by counting the number of customers at a local diner on a game-day (for a point of comparison, you can also collect numbers on non-game days). What would be the economic impact if the school closed and those games no longer happened? Also estimate the loss of school-related jobs that could come with closure. Which local residents are currently employed by the district? What would happen to them? What other jobs might be lost with school closure (e.g., if the grocery store closes due to lack of business, how many employees would lose their jobs?)? Lay out the long-term economic impacts of closure, too. Businesses are rarely willing to relocate to a community without a school, and research shows that housing prices and income are positively related to having a school nearby. Finally, find someone who can speak at a more regional level to the impact. This might be someone at your university extension school or regional development office or an industry expert. Invite them to speak at meetings to inform community members of the possible economic impacts of closure, or testify at hearings.

- Local impact on extracurricular and parent involvement. Survey families. How many don’t have cars? How many have jobs that would prevent attending school meetings or conferences at a faraway school building? How many kids might not be able to participate in sports or afterschool clubs if the school shut? Also ask coaches and club leaders to estimate what closure might mean for the participation of their athletes/members.

- Local impact on outmigration. Population decline is a condition (often, one created by policies), not a foregone conclusion. Many shrinking communities have rebounded from decline. But closing a school in a recovering community can seal its fate. Visit Census.org to look at population trends—local and regional—over time. What would school closure mean for trends at this particular moment? Few people or businesses are willing to move to a town without a school. However, frame these data carefully. If your town is losing population, some might interpret this as a reason TO close (if you’ve been losing people over time, what does closing the school matter?)… so focus on how closure may stop a recovery.

- Local political and social impacts. Rural schools can be an important source of political power and social activity. Document how local residents use the school and what it means to them. Count the crowd at the local Christmas concert, for example, or survey residents about where they see each other and how they get involved in their community. However, depending on who you are making your case to, be cautious about talking about how the school is a source of political power. Unfortunately, many policymakers know this, and the desire to close your school might be an attempt to weaken your political power.

- Dispute the pro-closure arguments. Oftentimes, the argument to close is based on faulty information or assumptions—especially the assumption that closure will save money. Explore the data that closure advocates are using to make their argument to see if they’ve gotten it right, and, if they haven’t, rerun the analyses for more accurate projections. Make these updated numbers widely available (e.g., op-eds, school board meetings, social media). Some common areas that are often inaccurate include:

- Personnel savings. Personnel is a district’s largest expenditure, so look at these numbers and claims especially carefully. For example, the number of administrators in the district may not be reduced with a closure, and, in places with discrepancies between teacher salaries, the higher rate must often be honored. Also, if the district is planning on letting personnel go, they must retain those with seniority, whose salaries are more expensive.

- Building capacity projections. States often have minimums on classroom square footage per student, and adding more students to the receiving school requires larger classrooms—an enormous expenditure. (Note that these space guidelines vary by grade level, too.)

- Transportation. Transporting students over longer distances requires more gas, and it might produce more wear and tear on busses. In addition to looking at cost arguments, also look at projections for bus ride length. Make sure that they take into account factors like the roads themselves (rather than as-the-crow-flies estimations), road conditions, and seasonal and weather-related road closures.

- State aid. If the school being closed is more isolated and remote, and if it receives state funding for its isolation/remoteness, that revenue might be lost with the closure.

- Access to education. Sometimes advocates argue that closure will increase access to extracurricular or co-curricular activities. However, if students from the closed (typically farther) school have no means of getting to and from those activities, then they won’t see a meaningful expansion of access.

Cut costs and increase revenue. The number one cause of closure is “fiscal strangulation”—that is, starving a district of the funds it needs to effectively operate. Maintaining sufficient funds is, therefore, essential to staying open.

- Share resources with other schools and districts. Small districts can partner to share administrators, like superintendent, assistant superintendent, kitchen supervisor, special ed director, school nurse, or administrative assistant. Nearby schools can share expensive specialized courses (like Career and Tech Ed and Advanced Placement), and then run buses to get students to schools where the courses are offered. Schools can specialize in different areas (e.g., arts, technology), but create agreements to make their curricula available to students from surrounding schools or districts. Regional education service agencies (often called cooperatives) can also provide programs like special education and career and technical education; these help rural schools gain economies of scale. Other rural districts have developed collaboratives that are aligned to the local labor market (see, for example, the Rural Schools Innovation Zone in Texas). These kinds of collaboratives can not only help districts run more effectively and efficiently, but they can also allow schools to better meet community needs.

- Adopt multi-grade classrooms. In multi-grade classrooms, one classroom and teacher services multiple grades. This has enormous pedagogical value, as younger kids get help from older ones and older ones learn the material better. It can also reduce costs in small schools. It can also provide some flexibility, as teachers and administrators might change the configuration from year to year based on grade-level enrollment numbers. Some schools also might also consider more of an “ungraded” approach, placing children in groups according to where the students are at individually. There’s a lot of research and writing on this topic; see these sources. This approach takes a strong teaching team, good professional development, and a lot of trust between school staff and the community.

- Use virtual education to expand course offerings. Your state may have a state-supported, accredited provider of virtual courses; other states run virtual courses through regional education cooperatives.

- Consider a four-day school week. Many districts—including many rural ones—have adopted a four-day week to cut costs and attract teachers, and in many rural areas, this reform is enormously popular. Be aware that research suggests that savings might not be huge, and evidence is mixed on the impact on student achievement (see this website for more information); however, one recent study showed that, for rural students, there might be no negative effect on learning of a four-day week.

- Investigate your state’s funding formula. Look to understand WHY your district is struggling financially. This is challenging: school funding is notoriously difficult to understand, and legal, policy, and funding experts can be helpful on this. But here are some resources to get started: a basic primer on state funding formulas, a general explanation of the equities of funding, state-to-state comparisons, background on which states adjust for rurality in funding, and an investigation of adequacy and equity. Some questions to investigate: does your state adequately fund its schools? Does it account for rurality in its funding formula? Are there large gaps and inequities between wealthy and poor districts? Consider filing a lawsuit (see below).

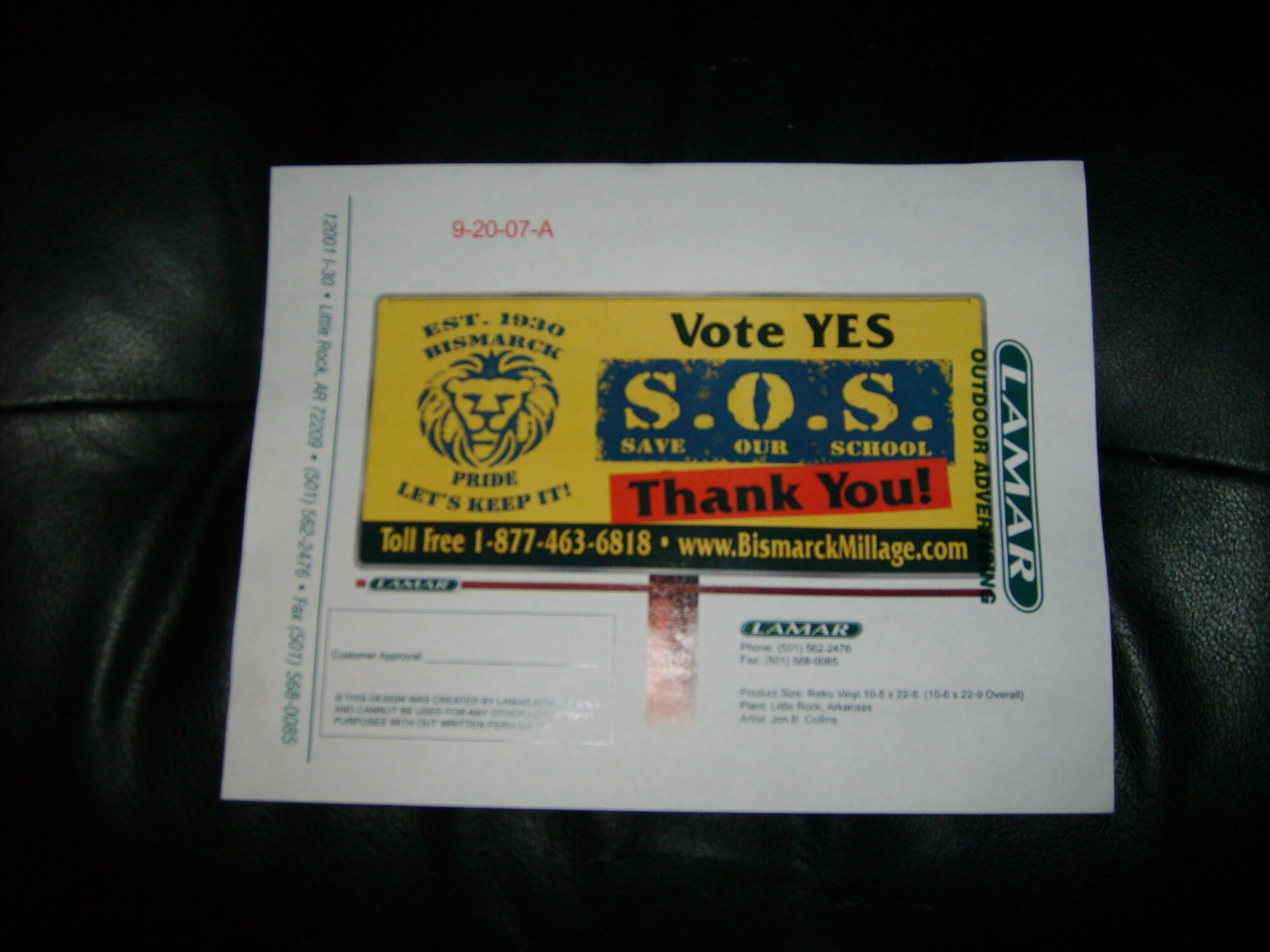

- Raise the tax rate locally. Raising taxes is always difficult, Many districts—especially low-income ones—are already taxing themselves at a very high rate, and many community members will resist a tax hike, often for good reason. So go this route cautiously, and be aware of the uneven impacts it might have. To persuade votes, describe (concretely) how additional funds will be used, how that will lead to keeping the school open, and how it will benefit even those families without students in the district (e.g., communities with schools tend to have higher home values and attract more business than those without). Short-term tax hikes are easier to swallow; if it will be a short-term hike, be clear about that timeline. This is an especially important time to listen to those opposed, understand their concerns and values, and speak to those concerns and frame your pitch in terms of those values. Couple larger informational meetings, forums, and community dinners with door-to-door and one-on-one meetings. When it’s time for a vote, organize carpools to get voters to the polls.

- Make short-term sacrifices. For a limited period of time, you can ask staff and teachers to do things like give up 2 weeks of paid vacation or cut salaries. However, these kinds of sacrifices, while they can be powerful testaments to employees’ dedication and care, are not sustainable, especially in an era of historic teacher shortages. Use these measures sparingly.

Boost enrollment. Boosting enrollment can increase revenue. It can also help districts avoid consolidation (in states with enrollment minimums) or meet facilities requirements (in states that mandate new facilities’ sizes).

- Understand the enrollment issue. Why are students leaving your school? Or not attending to begin with? Talk to families about what’s motivating this, either through one-on-one conversations or surveys. Then look at the responses: is this something that can be changed? There might be times when you don’t want to change—or can’t change—whatever is causing the leaving. But if it something like lack of a sports program, this is good to know—and, potentially, changeable.

- Distinguish your school. In states with school choice, make sure your school’s mission is clear and distinct from neighboring schools’ missions. You might also consider recruiting local students to return to your school by hosting information sessions, posting flyers in public places, even going door to door.

- Count the students choicing out. Many states with school choice limit the number of students that can “choice” out of a district. Make sure you have an accurate count of students that are zoned to your school but are not attending it. You can go door to door to count the children and record whether they are attending the local school, or you can talk to bus drivers, who might know which houses have children that appear to be attending schools out of district. Also look for school buses from other districts that are illegally running. Figure out where the violations are happening: is your superintendent allowing too many transfers? Is another superintendent illegally running buses? Are families filing false housing information to appear as though they’re living in another district? This information can be reported to the state. Documentation (e.g., photos) can help.

- Seek resources for part-time students. Your state’s funding formula might provide some funds for students attending part-time, or part-time students might be counted in Average Daily Membership/Attendance counts. Therefore, you might be able to have some part-time students (e.g., homeschoolers) taking specialized classes. If you offer these classes in the middle of the day, they might also be counted in nutrition reimbursements. Inventory your current teachers’ skills to understand what special classes they might be able to offer. See this resource.

- Host international students at your school (see this story). Public high schools can apply to the federal government to enroll international students. Or local families can apply to host international students (who then attend the local public school) through a program like High School in the USA, Academic Year in America, or others (do your research—find a reputable organization!). However, use this approach cautiously, as it can be challenging to meet all students’ needs and expectations.

- Pay attention to new charter schools opening. A new charter school can drain a traditional public school of students, lower enrollment, and cause closure. But most states require some sort of public input, so use that opportunity to turn up as a community and voice any concerns. You can also be in touch with local legislators and your state’s Board of Education.

- Know your numbers. Pull information from your state department of education website to understand your school/district’s enrollment. States have a data dashboard that includes information about things like enrollment, demographics, and test scores. For enrollment, look at trends over time to see if, for example, dips are yearly blips or more serious and long-term declines. You might be able to persuade taxpayers to raise taxes for a few years, if it’s understood as just a temporary measure to account for a couple of years of lower enrollment.

Focus on academic quality. Not only is a strong academic program essential for providing students with a good education, it’s harder to shut down an academically thriving school. People will also move to an area for a high-quality school and pay higher taxes to support one.

- Focus on teacher quality. Teacher quality becomes even more important when you have a small school, especially if a student might have the same teacher for multiple subjects or multiple grades. Work to hire and retain high-quality, community-oriented teachers.

- Partner with a local community college to support dual enrollment. Dual enrollment allows high schoolers to take classes for college credit; this increases the number of courses available, and, for students that attend college, it can make a college degree less expensive and faster. Research shows that dual enrollment increases high school graduation rates, college enrollment rates, and college completion rates. Dual enrollment programs also tend to be cheaper to run than AP courses, and many states have funds available to offset college tuition costs; your state’s department of education website should have more information.

- Start a grow-your-own teacher program. With grow-your-own programs, community members (youth and adults) are supported to gain experience and knowledge to become certified teachers. Some programs target parents, para-educators, and volunteers; others are geared toward high school students. This can be a great way for talented individuals (who care about the well-being of local children) to enter teaching. Also, many states are still operating under Covid-era rule changes that decrease the formal credentials required for teaching; it’s easier to get an emergency license right now. However, your school must have the capacity to support the onboarding and ongoing learning of new teachers, as teaching demands not just love but also specific teaching skills and content knowledge. Many states have organizations that help build these programs. Search to see if your state does.

- Seek out grants to strengthen the school’s academic and extracurricular offerings. Many federal, state, regional, and local organizations offer grants for resources, like technology, and after-school programming. Writing a strong grant application usually requires some expertise, but some grant applications are simpler than others. Also, you might be able to find a local community member willing to volunteer their time and knowledge to help draft an application.

- Recruit strong teachers from local universities. Go to local campuses to meet graduating students. Talk up your school and community. District leaders could hire graduates in groups so that they have a cohort of support. Partner with the chamber of commerce to offer financial incentives; for example, local landlords might be willing to reduce rent for young teachers.

Prioritize family and community engagement in the school. Not only does strong community engagement boost academic quality, it also makes the school a prized local institution—one that people don’t want to see closed.

- Build school-community partnerships to offer after-school and extracurricular opportunities that the school cannot afford (e.g., book clubs, parent engagement clubs, theater clubs, talent show, art show).

- Incentivize community volunteering. Volunteering not only saves money, but also ensures community members know what’s happening in the school, often making them more likely to support bond issues, tax increases, etc. One community in Vermont offered elderly volunteers $5 tax rebate for every hour they volunteered. Volunteers logged their hours, and they could earn up to $2,000 in tax rebates (the town passed a bill to set aside a fund to support these tax rebates). In places where many elderly residents go hungry, offering volunteers a school-provided breakfast when they volunteer might be effective. Also, some civic organizations require that members volunteer; partnering with these local organization can help their members put their volunteer hours toward the school. Volunteers can do things like provide one-on-one help in classrooms, work with struggling readers, make copies, shelve books, sit at the front desk, or monitor halls. One good model for this kind of program is the Parent Mentor Program, used in both rural and urban schools across the country.

- Make sure school staff hears and responds to families’ concerns. If concerns are widespread and go unaddressed, this can lead to student and family disengagement, decrease academic quality, and also make families pull their children from the school, dropping enrollment and reducing funding.

- Open school for community use. The school should be a community institution. Many rural schools allow families and community groups to utilize the school space during after-school and low-density hours. This can build trust between community and school, and it brings community members into the school.

- Consider creating a community school. Community schools are schools that provide services to address community needs, such as medical, mental, and dental healthcare. Providers are often eager to site their services at schools, and offering school-based services can build trust between school and community, improve school/community communication, lower absenteeism, and generate revenue. For more information, see the Coalition for Community Schools website.

- Offer school-based services for non-parents and other adults, such as adult education classes (e.g., GED classes, English/ESL classes), a food pantry, use of school site for community and family functions.

Consolidate carefully. School district consolidation does not have to mean closure. However, it often does, as the larger, more powerful, receiving district has the leverage to close the smaller, less powerful school(s) in the consolidated district. Thus, you need to put specific protections in place that guarantee all schools stay open.

- Hold district leadership accountable. Prior to and during consolidation, be cautious about the possibility of back-door dealings between superintendents and/or school boards. This can include such as unwritten financial promises (e.g., to build one school a new stadium, which can gut the district’s budget) or handshake agreements to close schools. Decentralization really only works with ethical leadership and a high degree of (earned) trust. Also, recognize that some moves are particularly likely to pave the way to district consolidation and school closure. Consolidating sports teams, for example, is one such move, as merging mascots can often be a major barrier to school consolidation.

- Consider administrative consolidation. If your district consolidates (whether forced by state policy or entered into willingly by the school boards), investigate the possibility of administrative consolidation, where through formal written agreements the school boards agree not to shut down schools (or, at least not without the vote of BOTH towns involved).

- Operate the schools in as decentralized a way as possible. Collaborate on shared services, ensure equity of resources, etc, but keep each school responsive to the needs of its individual community. Some districts in Vermont have also adopted a structure where each former district has a small elected group that makes more local decisions, like developing a budget, and then brings it to the larger merged school board for approval.

- Deconsolidate. Many states have guidelines outlining a process by which a community can detach from a district; deconsolidation might be especially useful for a community that had been forced to consolidate and is now facing school closure. Investigate whether your state has a policy (or policies) governing this process.

- LINK to this resource from Jerry Johnson and Hobart Harmon about how to navigate consolidation.

Make school closure an election issue. Campaign for and elect leaders that understand the threat of school closure and have a proactive plan to stop closure.

- Contact your elected leaders—by phone, email, social media, and face-to-face. Be clear and specific about why you oppose the closure of your school and what action you want them to take.

- Hold local leadership accountable. Closure is not just an issue for school leaders to worry about. Make sure that town leaders also have a plan, and that they’re willing to work with school leaders to address any potential threats to the school (e.g., declining enrollment, fiscal distress, academic distress). In debates, ask questions about their plans.

- Contact your elected state legislators. These legislators represent you and your community; reach out to them often. Make sure they understand your community’s concerns about closure. Individual lawmakers can also always propose bills to save individual schools or change the conditions that lead to closure—so make sure they are working for your interests! If they’re not supportive, make this issue central to their re-election campaign. Legislators can also speak persuasively to local election issues (e.g., if closure is a matter to be decided by the school board).

- Find new candidates. Encourage people (with both the expertise and will to fight closure and the policies that cause it) to run for election. Even the threat of political defeat can be enough for a school board member, town council member, or legislator to reconsider their vote.

Change policy. Sometimes the only possible course of action is trying to change the policy that is forcing a school to close. If that’s the case, you’ll need to organize for a statewide campaign to change state policy.

- Look for double standards. Policymakers often allow for double standards when closing schools. Be aware of which school is being closed and which isn’t, and call your legislators on that. Why are schools that serve more rural, poor, or Black and Brown students subjected to closure when more urban, wealthier, and Whiter schools aren’t? If a policy creates uneven outcomes, it’s discriminatory and needs to be changed.

- Push to change your state’s funding formula. Many states offer additional funding to small, rural, geographically isolated, and/or poor schools or districts. (It might be helpful to get this funding linked to individual schools, rather than districts, so school boards have less incentive to close schools.) For many years, Kansas had a unique formula, in which it took into account population density, and it provides extra funding for the sparsest (i.e., rural) and the densest (i.e., urban) districts. Vermont also gives extra funding for geographic isolation, poverty, English Language Learners, and other factors that can bring more support to rural, remote, and hard-to-staff schools. (This article shows which states account for sparsity, small enrollments, isolation, or increased transportation needs.) Think about alternatives that a broad coalition of similarly under-served districts will likely support. Other states have revenue sharing approaches, where local resources are pooled statewide and redistributed according to level of need (see Vermont’s approach) Some states use three-year rolling average of enrollment for funding purposes (instead of a single year’s enrollment numbers); this prevents major drops in funding due to a one-year low enrollment. Though some states have turned to sales taxes, be very cautious about this approach, as sale taxes typically disproportionately impact those with the lowest incomes.

- Use state ballot measures to provide schools with more resources, such as increasing taxes on the wealthiest households (with that revenue going to schools) or dedicating casino revenue to education funding. See this article for some ideas.

- Organize to make the closure process more transparent and collaborative. In some places, the process for closing a school and/or consolidating a district is especially un-democratic. But this can be changed. For example, you might require votes from both the closing and the receiving community before a merger. Some states require both school boards to vote to even bring it to a community vote; other states require studies researching the impact of consolidation as a part of the process. (And some states, like New York, require all of these things!) Other places require a super-majority vote (that is, some threshold more than the regular 50%) on issues related to facilities. (The downside of this, though, is that it be harder to pass bond issues for school improvements or new buildings, which can then cause closure.)

- Create a statewide coalition. If you’re looking to change state policy, you’ll also need a statewide coalition to share information, mobilize people, and pool resources. Consider creating a network for sharing information quickly and for getting people to turn out to events (google groups can be useful for superintendents sharing information, for example, while social media is great for mobilizing the public). Use these platforms to share stories, plan events, and help one another. To share resources, create a nonprofit so that you can raise money (or find a nonprofit that is willing and able to make this their central issue). You need to get communities and school boards to set aside money toward this issue; consider a membership model, where each member organization/community pays dues to cover shared costs. Have a volunteer board that will decide how the money gets spent.

- Understand the process for advocating for or commenting on legislation and other regulations. On your state government’s website, there will be information about how bills become laws, what bills are being considered during any legislative session, and the procedures that govern other regulation changes (such as state department of education rules). There are typically official periods for public comment on bills and regulations, but there are other opportunities and avenues for making your voice heard (e.g., protest, mass mailings to legislators, etc).

- Turn out for public hearings. For proposed legislation (or changes to existing legislation), there will be public hearings. These meetings are open to the public, though there are rules about testifying (e.g., how long a person can speak for). Familiarize yourself with these rules (which are posted on your state’s official website) before attending the hearings. People often find it most helpful to write out your thoughts beforehand (and to practice!). Because your time to testify might be limited, plan to attend as a group and plan who will say what. Testimony from youth might be particularly persuasive.

- Stay in constant contact with your elected state representatives; this is especially critical if they will be involved in a vote to change policy related to closure. Flood them with letters, email, and phone calls. They’ve been elected to represent your interests, so make your interests known. Invite them to community meetings for more informal dialogue, as well as a chance for you to make your case to them directly.

- Hire a lobbyist. A lobbyist can influence and change policy at the state level. They can help you build a campaign and then effectively communicate with legislators and staff, and your opponents (e.g., those opposing increasing education funding) likely have them. However, lobbyists are expensive; this might be an expense a statewide coalition can work to cover. If you have an effective campaign, you might also considering hiring the lobbyist only for their statehouse and strategy expertise.

- Consider a waiver. If policy change is not possible, consider a waiver process that would allow districts/schools apply for exemption from the policy, including those that have strong academics and/or sound finances. However, understand the equity implications of such a policy; it’ll be the poorest, most rural schools that either do not make the exemption criteria or do not have the infrastructure to write the application.

- Extend charter school flexibilities to traditional public schools. As states adopt more and more choice/charter-friendly legislation, you might be able to make a case that the flexibilities offered to charter schools should also be extended to traditional public schools. Look to see whether the policy that’s leading to closure applies to charter schools; if not, see if that same flexibility can be offered to traditional public schools. See this related story in Arkansas.

Persuade the state board of education. In some states, a state board of education might have to approve a contentious decision to close a school. Then it’s the state board of education members that you’ll need to persuade.

- Know your state’s law so that you understand when a closure decision might require state review.

- Turn out for public sessions. If state review is required, there will probably be a hearing with public input. Pay attention to the rules for participation and then organize who will say what and how. Include students who can speak to the impacts, and caravan to bring out as many people as possible!

- Persuade the state board of education to meet in your community. (Look at your state government’s website to see rules and regulations about where hearings can be held.) Policymakers find it harder to close a school when they are actually in the community, sitting among families and students, and listening to their stories.

- Learn about your state board members. Many state board of education websites have information about each board member. Look at this (or Google them) to find out more about each. Given their background, what kind of arguments are they likely to find persuasive?

File a lawsuit. Closure is filled with inequalities and injustices, and it’s typically an un-democratic process. Sometimes a lawsuit might be the only option, especially if a community’s educational or civil rights are being violated. However, litigation is often not successful, it can be costly, and it may invite retaliation. Use this as a last resort.

- Build a coalition. Get other districts to join the lawsuit and put money toward it. Then, even if you lose, you might have created the publicity and fuss to make a legislature back off (or consider a more cautious approach). However, if you’re considering filing a lawsuit, be aware of the potential effects. If a court declares a funding formula unconstitutional, for example, they will force the state’s legislature to adopt a remedy. Thus, you will still need to win the fight legislatively, to ensure that the legislature adopts a new funding formula that is both equitable and adequate and that doesn’t involve the closing of school buildings. So make sure you’re organizing for the policy fight while simultaneously fighting on the legal front.

- Watch carefully. Make sure that decision-maker (e.g., school board members, legislators, state officials) follow all the rules during closure proceedings. There are regulations that govern the closure of a school building; these are spelled out in state statute. If you can demonstrate that there was a violation, you might be able to bring a successful lawsuit.

- Fight discrimination. Closures disproportionately impact low-income communities and communities of color. If you can show a racial or class-based disparity in a policy’s impact, you might be able to challenge the policy for violating the education clause in the state constitution, equal protection clauses or civil rights.