One way to think about school closure is through the lens of spatial justice. Resources are unevenly spread across geography, typically so that wealthy suburbs have more than poorer rural and urban areas. Take, for example, food deserts. Food deserts are places where it’s hard to get affordable and healthy food because there’s no grocery stores or supermarkets nearby. Nearly 13% of the U.S. population live in a food desert, and low-income communities—in both rural and urban places—are disproportionately affected. We see this unevenness with others resources, too, like access to the internet or clean water or affordable housing.

Schools are no different. Every year, schools are closed in thousands of communities across the country. Recently, many of these closures have been in large cities, like Chicago and Oakland. But, much more quietly—and for much longer—rural schools have also been closing. This leaves these rural places without a school, limiting students’ and families’ educational access and removing an important community institution.

Why does closure happen?

School closure is usually justified by one (or more) rationales. The first is cost. Policymakers sometimes close schools to reduce costs, often because they’re facing a budget crisis. This justification is particularly common for rural closures, as leaders seek to “maximize” resources over small populations. The second is academic performance. Policymakers close “failing” schools, usually in response to low test scores. This rationale is often described as holding teachers and leaders “accountable” for poor performance. The third is equality: policymakers sometimes argue that school closure can provide better educational opportunities to students, especially low-income, Black, Brown, or rural students.

With all of these rationales, it’s important to note two things: 1) they’re often unevenly applied (e.g., one school with “failing” scores will be closed, while another with the same scores won’t be), and 2) research does not support many of the assumptions they depend upon.

How does closure happen?

In rural areas, one of the most common causes of closure is district consolidation. District consolidation (that is, the collapsing of smaller districts into larger ones) is usually justified by efficiency and equality arguments, and it often leads to school closure, as the new, consolidated school board looks to save money by closing facilities, usually in the consolidated or annexed district. Many states have policies that mandate or incentive district consolidation, often tied to minimum enrollments, financial incentives, or facilities funding linked to enrollment or student/staff ratios.

Another common trigger of closure relates to budget constraints. Unfunded curricular or staffing mandates can force districts to look to cost-saving measures, including closure. Similarly, school funding court cases have led to closures, as officials look to offset inequities in

state funding; this has led some states to adopt construction and facilities regulations that incentivize or force the consolidation of districts and/or the closure of schools. Any factors that reduce enrollments can also raise budgetary concerns, and, currently, the end of Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund money, coupled with pandemic-related enrollment drops, is also forcing some districts to consider shutting sites.

Other policies have also played a role in closure. Many states have adopted measures allowing school closure as an academic sanction (i.e., a punishment for poor performance); closure is also a common “intervention” model used in many states’ “school improvement” plans. Some researchers also link the expansion of charter schools to closure, by either reducing enrollment in or funding for traditional public schools. Closure can also happen as a result of state takeover.

The process of closure is often undemocratic. The decision to close is typically made by district or state meetings, often with little community input. Even when there are forums or meetings to solicit community feedback, community members often feel as if the decision has already been made. They did not close their schools; instead, their schools closed on them. Residents also sometimes feel as if their school had been “set up” to fail, often due to inadequate funds or resources. Research also shows that closure criteria—when they exist—are sometimes unevenly enforced, and schools that don’t meet criteria are still closed, while others—often wealthier and Whiter—that do meet criteria are overlooked.

Who does closure affect?

Closures affect communities across the country. But they are not evenly distributed: they tend to hit both urban and rural places that are already overlooked and under-resourced. Their impacts on rural communities, in particular, can be seen in the impacts of Arkansas’s Act 60, an act that mandated the consolidation of districts that fell below 350 students. When it was in effect from 2004 to 2023, it led to the closure of more than 100 rural schools across the state. This map, created by Christine Murray at Bates College, shows closures forced by Act 60 by year, demonstrating the magnitude and reach of the impact. (*Please note: this map only includes closures between 2004 and 2023; it does not show ones that were caused by Act 60 but closed in subsequent years.)

It’s important to recognize that closures also disproportionately affect low-income students and communities, and mass closures affect regions with declining economies and high poverty. Research also shows that closures are more likely to affect communities of color. This unevenness was also seen with Act 60: though the policy closed schools in all types of communities, it was more likely to close schools in low-income and Black communities.

In rural places, school closure had been linked to the decline of traditional rural industries (like coal mining and timber) and the mechanization of agriculture. These trends reduce jobs, limit state and local revenue, and force people to move.

What does closure do?

The effects of closure have not been well-studied, especially for rural students and communities. But the research that does exist suggest that closure has a variety of effects on students and communities. In the short term (the year before or after closure), it tends to lower students’ test scores and grade-point averages. The long-term impacts appear to be highly related to the academic quality of the school students are sent to. If they’re sent to a stronger school, they show gains. But oftentimes students are not sent to a higher performing school, even when the closure is motivated by academic concerns, and students sent to a similar or lower performing school experience declines in test scores. Recent research on school closures in Texas shows that students involved in a closure experience a drop in test scores, though those scores recover within a few years; however, it also shows longer term reductions in obtaining a college degree, employment, and earnings, especially for students from low-income backgrounds.

It’s unclear whether closures caused by consolidation, specifically, leads to academic gains or opportunities for rural students. Rural students might have access to more classes through closure, but no research shows whether students are able to make use of those opportunities. Also, larger schools tend to have negative impacts on student achievement, suggesting a trade-off between the opportunity for more classes and the effects of school size.

For rural students, closure is often associated with longer and more dangerous bus rides; these effects are especially pronounced for low-income students and students of color. Also, the longer distances associated with closure can also mean students are unable to participate in extracurriculars (even if their new school has more options) and families cannot engage in school.

There are very few studies investigating the impact of closure on the district’s budget. What research does exist shows that closure usually doesn’t save as much money as promised, often a very small fraction of a district’s budget. (This is because closure usually doesn’t meaningfully reduce the number of teachers or administrators, which is a district’s largest expense. Transportation expenses also go up significantly.) Related, studies show that district consolidation may not be cost effective, and savings might depend upon district size.

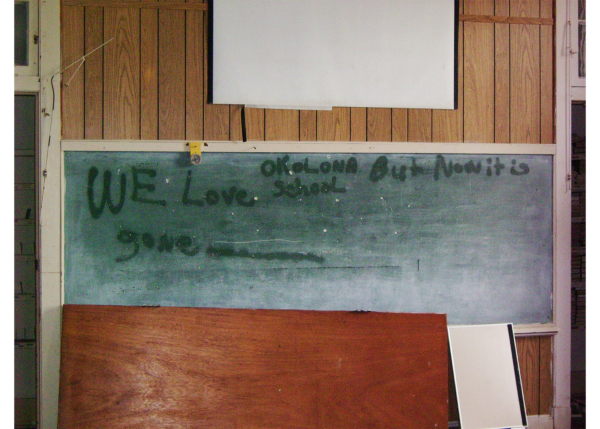

The impacts of closure on a rural community can be significant. It’s the loss of an important community institution, and buildings often go unused. Closure can force other local businesses to shut (e.g., diners, gas stations, or groceries that depended on school traffic). Research also shows that towns without schools have lower home values, greater income inequality, and higher child poverty rates. Residents also report a negative impact on social ties within the community, and closure is associated with population decline. When associated with district consolidation, closure can also reduce a community’s political voice, as it eliminates a local school board.

Not all school closures are unjust. Closure can be community-initiated and responsive to community needs and wishes, and it may expand educational access. But when closure is forced upon a community—whether mandated by policy or caused by a result of policy-created conditions—it is unjust. When it is “done to,” rather than “done with,” a community, it is unjust. When it disproportionately affects low-income communities and communities of color, it is unjust. When it denies a community of its right to determine its own future, it is unjust.

But we can fight back.

For a more comprehensive list of citations and more information about the work referenced here, please see “Rethinking the school closure research” by Tieken and Auldridge-Reveles.